British artists, they say, are like London buses. You wait for ages, and then two come along at the same time.

And the problem is, that you cannot help but contrast them.

The winner is …

The Tate has a gorgeous exhibition at the moment, peacocking two of the greats, Turner and Constable. They were contemporaries, rivals, and compared, even in their lifetimes.

I’m not going to do a review of that aspect of the show. I’ll declare my hand from the outset: it’s an unfair comparison. I go from a roomful of Constables, where I’m deeply impressed, to a roomful of Turners, where I am blown away.

It’s Sense vs Sensibility. It’s Roundhead vs Cavalier. It’s Gladstone vs Disraeli. It’s Salieri vs. Mozart.

Turner just dazzles. He stuns. And this exhibition doesn’t even include The Fighting Temeraire, or Rain, Steam and Speed.

So let’s admit it’s an unfair fight. Constable is one of the greatest painters Britain has ever produced. Turner is one of the greatest that the world has ever produced. Just like we can’t really assess Christopher Marlowe or Ben Johnson unless we close the door on Shakespeare, I don’t think we can really assess Constable unless we close the door on Turner.

So let’s do that, and then turn to the quieter, proper admiration of Constable.

The Christian artist

Because for readers of this blog, Constable has a deep affinity. He was an orthodox, straightforward Christian, and that seems to have impacted his art.

And that creates an interesting tension today. While I don’t think that it’s Turner’s tempestuous, eccentric morality that makes him so popular (though it can’t hurt), Constable’s quiet orthodoxy puts him out of step.

Constable’s quiet orthodoxy puts him out of step.

Even as generous and sympathetic a reviewer as Bendor Grosvenor has to acknowledge that this aspect of Constable is out of reach even for him, let alone our more secular age (you can listen here)

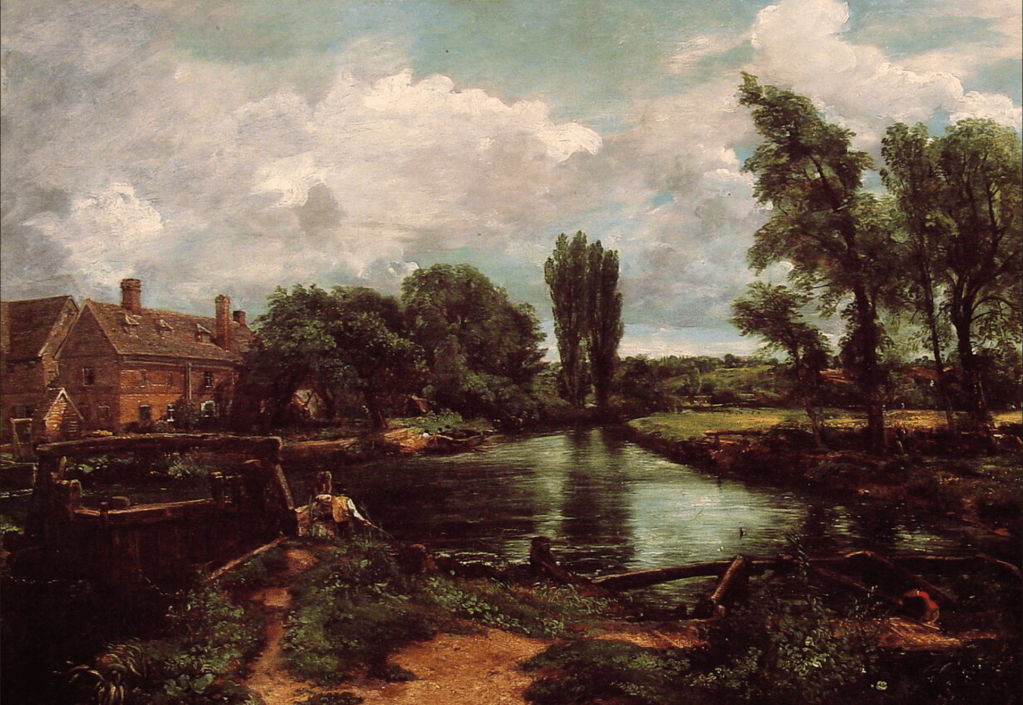

If you can call a Constable to mind, you’ll think of something like The Hay Wain, or one of the Flatford Mill paintings. Six-foot wide works in oil, deeply immersed in the English countryside. He loved the part of Suffolk where his family came from, and most of his large work seems be a profound study of that part of the world, carefully observant of the time of year, the time of day. The plants, harvests, weather patterns, water, are studied and loved with great accuracy.

Flatford Mill from a Lock on the Stour

One of the great parallels in the exhibition is therefore of two Constables. This is well known, but there is a demonstrable difference in style between those grand finished works, and his studies, his notebooks, his sketches. His quick watercolours to catch the clouds, or the Lake District, are quite beautiful in their own right, and possibly more pleasing to a post-Impressionist culture like our own.

Rainstorm over the sea

There’s a brilliant sketch, Rainstorm over the Sea, which shows brushwork we’d more easily associate with Bacon or Auerbach.

Pause there a second: both these men stand at a cusp in the development of painting. If someone back then were to work in the open air, painting landscape from life, then watercolours were pretty much the only option. Oils were sticky, required a lot of work to manufacture, and could only be taken out of the studio stitched in pigs bladders. Constable and Turner both lived through the invention of tubes of oil paint, making the medium portable and easy. They were both still studio painters (those large canvases are difficult to lug round), but they had a freedom which a previous generation could not have known.

We live so long after the invention of the paint tube that we expect freshness and spontaneity, and criticise formality. Turner moved easily into a new style to reflect that; Constable, I think, struggled. And that might be why one reason Turner is more easily admired.

Close the door on Turner again.

Constable looked, understood, and recorded. That makes him sound plodding and workmanlike – that’s my fault. His meticulous care was a work of deep love, and more than that, of an awareness of his part of the world as the Creator’s creation, to be known on its own terms as a profoundly beautiful gift.

Bendor Grosvenor says that Constable’s work is quite sensory – when he’s in front of one of them he can almost heard the birdsong, the wind, the water. The quiet countryside comes alive under Constable’s brush.

And it’s true, that when you set Constable among his fellow landscape artists, he shines. His contemporaries were overshadowed by their Continental masters, especially Claude. Water, sunsets, classicism, and a Mediterranean light set the theme, and they tried to copy that.

Constable’s genius was to make England look like England. Damp, grey, and northern maybe, but unmistakably here. Unlike Turner, he never travelled, and turned away from the French master. Turner, by contrast, both adored and challenged himself to surpass Claude. If you’ve never looked, the National Gallery permanently displays two Turners, Dido building Carthage and Sun Rising through Vapour, which Turner bequeathed on the strict condition that they should hang alongside Claude’s Landscape with the Marriage of Isaac and Rebecca and Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba. He invited the bravura contrast.

Close that door again.

Constable’s rich greens, dark pools, gentle horses, speak of another land.

Constable’s rich greens, dark pools, gentle horses, speak of another land.

And when you look, you can see the repeated motif of a church spire. Hiding behind trees, or even deliberately central, as if to say that it’s not merely another feature of the landscape, but central to Constable’s understanding of what a landscape is. A gift, received by faith.

Does that mean that Christian art has to be in this line of realism? I don’t think that follows at all. I know that the great Christian art critic Hans Rookmaaker argues something like that, but I disagree. There’s no reason we can’t paint dreams, patterns, emotions. Realism isn’t ‘the’ Christian style.

Nor is enjoyment of creation a uniquely Christian gift. Ask David Hockney.

Enjoyment of Creation as a known gift from the loving Father of our Lord Jesus Christ is a uniquely Christian insight.

But enjoyment of Creation as a known gift from the loving Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, well, that is a uniquely Christian insight. That enjoyment can take delight in line, in colour, in texture, in form, in pattern, in paint itself – or in the accurate depiction of a passing cloud.

England, their England

Now, there’s a trap here – and it’s one that generations of chocolate boxes have fallen for. A trap of nostalgia. Constable’s landscapes are pre-industrial – just. There are canal boats, maybe containing coal or pig iron, but they’re hauled by horses and young men. Harvests fill up wagons. Watermills creak and groan. It’s impossible that Constable didn’t know that this world was passing even as he painted, but he himself caught it from life. He was immersed in it, not nostalgic for it.

When prints of The Hay Wain or the White Horse hang on a million walls, they’re often there for a subtly different purpose. More seriously, when there are second- or third-tier versions, made for jigsaws or biscuit tins, they are genuinely made to be fake-nostalgic, to capture an England that never was, and no-one ever lived in.

Note for overseas readers: you know this, but ‘England’ and ‘Britain’ are not the same thing, and at this point need to be carefully distinguished. ‘Welsh’, ‘Scottish’ and ‘Irish’ identities are complex, but very different, and the nationalist identity I’m describing here is determinedly ‘English’ in profile. Constable’s landscapes are precisely located in England at a passing moment in time, which lays him open to being hijacked to support a particular identity, pre-industrial and pre-mass-immigration. Turner’s more pro-industrial and more European work (especially in Italy) make him much less prone to that.

We live at a time of rising hostile nationalism across a number of countries, and one of the fuels for that is a weaponised version of that sentimental nostalgia, a fake nostalgia. So although it should go without saying, it needs saying, that the gospel demolishes nationalism by creating one new humanity. There can be a right place for patriotism, but not if it is built on a hatred of ‘the other’. Constable, as an ordinary orthodox Christian, would agree with that.

It also needs to be said, therefore, that the bible refuses to be nostalgic. Here’s Ecclesiastes 7:10 – Do not say, ‘Why were the old days better than these?’ For it is not wise to ask such questions.

Sentimentalism, nationalism, and fake nostalgia are not gospel fruit – hope and faith in the New Jerusalem are.

Sentimentalism, nationalism, and fake nostalgia are not gospel fruit – hope and faith in the New Jerusalem are.

So we (English people) need to find the ways to take pleasure in Constable without feeling we are wrapping ourselves in a tribal flag to do so. He was one of those great painters who caught one aspect of his time so well, and we can enjoy him for that.

Gold

There’s another contrast to note, though, within Constable’s work.

He struggled to adapt towards the end. He was trying to catch that elusive spontaneity and freshness, and his way was to use lots of sparkles of white paint to indicate highlights. Critics called them his ‘snow’, and it does look artificial and strenuous.

But.

Constable exhibited in Paris. In 1824 he showed, among others, The Hay Wain, View on the Stour near Dedham, and Yarmouth Jetty, and he won a Gold Medal at the Salon for The Hay Wain and The White Horse.

The White Horse, or A Scene on the River Stour

I think that’s really interesting. Because the common myth is that the Paris Salon and the Academie behind it were only concerned with ‘finish’ – the high gloss style where skin is smooth, muscles ripple, armour glints and not a line of brushwork is seen. Hence, so the story goes, in time they couldn’t see the impressionists for what they were.

But look at White Horse. It’s a large familiar landscape, Constable territory, and the animal itself is relatively small, towards the bottom left. It’s being transported down-river The paint is scumbled, streaked, dragged and raw. There are peaks of it, and you can see the mark of the bristles. Look around at his other work – that oil sketch of rainstorm over the sea – and you can see an astonishing freedom. You can see the paint as paint.

And yet he won the Gold Medal.

We know that that Salon exhibition profoundly affected Delacroix, and that studying Constable was a key moment for him. And so the line of influence began towards Courbet, Manet, Monet, the famous Salon des Refusés, and Cézanne.

Both Picasso and Matisse repeatedly said that Cézanne was “the father of us all”; Cézanne himself said, “We are all in Delacroix.” And Delacroix found himself and his style while looking at a white horse waiting patiently on a flat barge moving down a muddy Suffolk river.

Constable proved to be far more influential than a little biscuit-tin reproduction might make you believe.

Constable proved to be far more influential than a little biscuit-tin reproduction might make you believe.

The most beautiful watercolour

Now, I’m going to open that door again, because Turner’s demanding to be let in.

It really is an unfair comparison. Someone once said that the weather posed for Constable, but it performed for Turner. I have had to teach myself to enjoy Constable, and I do enjoy him. But I didn’t need anyone to teach me to be blown away by Turner.

I’ll underline it just once more: The Blue Rigi, Sunrise might be the most beautiful watercolour anyone ever painted.

The Blue Rigi, Sunrise

Have you been to see them?

Have you wondered why non-Christian Turner is more popular? Or have you seen fake-nationalism grabbing Constable with nostalgia?

Pile in!