Thomas Heatherwick is a designer, and arguably the most influential in Britain at the moment.

He was the man who designed the gorgeous Cauldron for the 2012 London Olympics (do you remember those magical, lifting petals in flames?), and – again in London – behind the lovely redevelopment of Coal Drops Yard, at the back of King’s Cross, and the new Routemaster bus. Head to his studio, and you’ll discover a stunning range of buildings, exhibitions, and objects, with a global clientele.

What Heatherwick is not, is an architect. And yet he designs buildings. Within that tension lies his latest book – and one that is a really stimulating read for pastors and teachers. By the way, if you pick it up in your local bookstore and think it’s very large and therefore long, crack it open and have a look. Thick pages, lots of useful pictures, changes of font – this is a book which has been designed, right down to the feel of the paper. This a quick read, with a simple argument.

Here’s his beef. And it matters to pastors.

The profession of ‘architect’ now owns the task of designing buildings. That’s a relatively recent phenomenon, but now a global truth.

As a profession, earning the title ‘architect’ has a formal training, several years long. That isn’t necessarily wrong, in Heatherwick’s view – in fact he argues for a very rigorous academic training. But a different one.

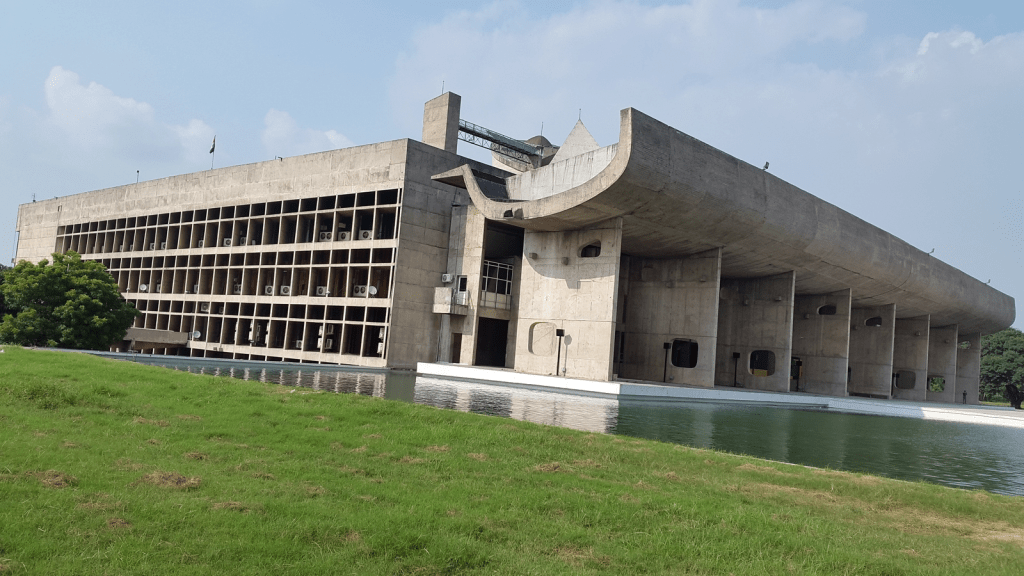

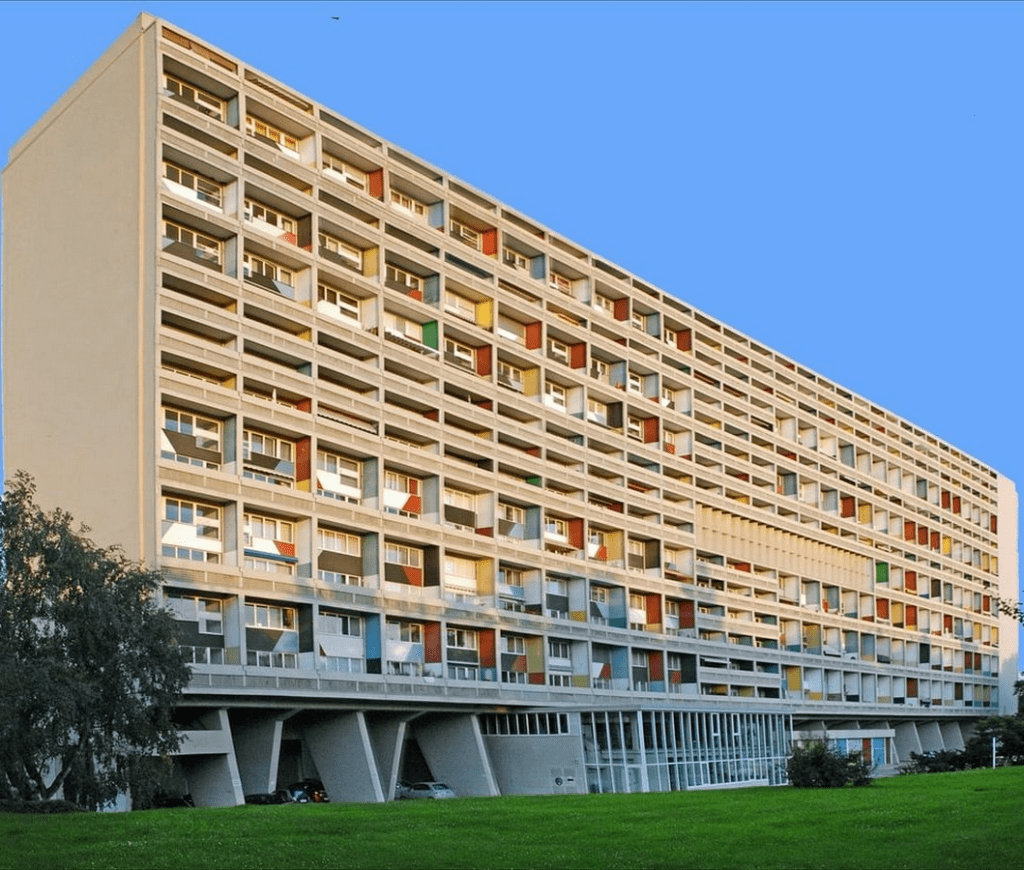

Because the current model of training, and of approved architecture, produces buildings that are soul-crushingly repetitive, vast, boring. A combination of the dominance of this one particular style, the Modern, with straight lines, perpendicular glass, and blocky high-rise buildings, originating in the presiding genius of Le Corbusier and now excluding all others, together with the industrialisation of that style, meaning that there are vast economies of scale in using the same steel, plate glass, lifts. Hence this one style is everywhere.

Both elements of this are important.

As a principle of design, Heatherwick finds this style de-humanising. It crushes us, with no sense of place or pleasure, and it bores us. Hospitals, offices, banks and department stores all share the same bland facade and interiors. So too do the flats (apartments) we expect people to live in. He usefully – rightly – finds Le Corbusier guilty of all manner of ugliness, yet in the process somehow persuading the architectural world that this style and is uniquely fitted for the twentieth century, in its plainness and starkness, and any element of decoration or deviation was populist and crude.

That is, this style is manifestly unpopular with the unarchitectural majority, but that only elevates the educated taste of the elite architecturally trained. It wins elite awards because only the elite recognise it as beautiful.

And as a principle of economics, Heatherwick finds it painful. The construction industry is one of the leading contributors to the pollution driving climate change, and yet the model is to have buildings with a shelf-life of twenty, thirty years before they need to be demolished and built again. How wasteful, he argues, when a little more thought could provide buildings that lasted well for a century and beyond.

He wants new design templates, new ways of manufacturing and constructing, which will produce interesting and lasting style. He’s not wanting to go back in time to the medieval guilds, but he wants us (you and me, the ordinary passers-by) to enjoy the buildings we use and walk past.

Now I reckon he has a series of good points in here which anyone might find interesting, but that’s for another review and another day. Why do I think this book is worth your attention as a pastor?

Building Projects?

Well, first of all, if you have a building project on the drawing board, you should tuck this under your belt and have a think. It might make you hesitate at the straight lines and clean steel you are being offered.

Look Again

Secondly, I think it should make us look again at the cities – and the churches – we inhabit. Apologies if you don’t live in a city, but there’s a fair chance you’ve also been impacted by the Modern or International style, even if it’s just your local supermarket.

He helps us read our physical culture – in which we preach, pastor and evangelise.

Where I live is a good example of what Heatherwick loves, and also what he complains about. And fortunately it’s a visible example, because seemingly every time there’s a news story about house prices (up, down, static) or mortgage rates (ditto), one particular photograph crops up – a view of the gleaming Canary Wharf in London, viewed past the Edwardian terraces of Muswell Hill.

Look at those houses, typical of the streets near here. Two developers, James Edmondson and William B Collins, were responsible for the look of the whole area, in a massive and simultaneous redevelopment. Houses, both large and small, multiple flats, flats over shops, were all built from the same pattern book, reusing dozens of styles of windows, doors, balconies and stairways. It was economical, but clever. There’s a harmonious style, but constant and subtle variation.

Now look past them to the towers of Docklands – glass, gleaming and monochrome. In one shot you have the double focus of Heatherwick’s thesis. Human, or boring.

It’s worth probing that, as preachers. What it does it say about and to people who live and/or work in either of those worlds, or who move between them? What does it say about whether they are intrigued, or enjoy themselves, or are fascinated? Do love this world too much? Or do they not enjoy a good creation?

It would be easy to say that this all comes down to money, but I think that misses Heatherwick’s argument. On the one hand, the City is not short of a bob or two. Those sheet glass curtains are not the result of extravagance and wealth, but rather of a false economy that refuses to do anything other than monetise space, and squeeze maximum profit from it. Curves, balconies, interest, take up space – and space is money. So even the global flagship buildings rise up and up, economising floor space at all costs. And the result is – with few exceptions – buildings that could be in New York, or Singapore, or Vancouver, offering neither place nor pleasure.

On the other hand, Heatherwick wants to see the reintroduction of what are called ‘Pattern books’; manufacturers offering a variety of everything from doorknobs to girders, with a huge variety of stimulating possibilities. At the moment all such pattern books are of the one style; they didn’t use to be, and they don’t have to be. You can have variety and economies of scale. Those Edwardian apartments show that.

I’d want to add church buildings into the mix. The central broadway of Muswell Hill had three churches built on it, all at the same time as the houses, and all in strikingly different styles. Where I am, the Anglican one, Is faux Gothic, with a tall spire, and a vast space inside. At the other end are the Baptists, in a turreted red-brick democratic space. And in between were the Presbyterians, in a flint and terracotta folly, with balconies and sweeping stairways – now a steakhouse.

None of those styles is remotely connected to the red-and white harmony of the area. Each of them is eccentric, and none of them uses a local style or indigenous materials. But each has a unique charm.

In other words, they give pleasure and they have a sense of place.

Heatherwick will encourage you to read your area, too, and think about what the buildings say.

Theology

Because, third, there is some theology for us to do.

There is an idea, prevalent from the Aussies a few years ago, that buildings are just rain shelters. Walls up, a roof across, what more is there to know.

But we are embodied beings, and the buildings we use affect us.

I moved to Oak Hill College just after a new academic centre being opened. I had been walked round the site while it was still a large (and expensive) hole in the ground, and I then got to explore it while the paint still smelt fresh. I saw what happened to students as they entered the building – it was light, and lovely. A library with gorgeous views and the sun streaming in – no dark and fusty thinking here. Lecture rooms designed to take learning seriously. Huge windows and doors which slid open to let the fresh air in, at full height. The students seemed to walk taller as they walked in – they are embodied beings, and the building was intended to make them feel like the pastor-scholars they needed to become.

Now, take a tour of your church building, and ask yourself what your building does to you. What does it teach you about what it is for? How is it meant to make you feel? Does it try to communicate anything about humans, or God, or the gospel? Is it a classroom, or a concert venue, or a TV studio, or a place for choral evensong, or – what?

Because every building is designed to do something, however bland or anonymous. And if it’s been well-designed, you will pick up on those cues, however subtle.

Critically, you will experience disquiet if the building is not being used in the way intended. I can think straightaway of three churches, which turned their meetings round 90’, to make better use of the space. I reckon they were right – but, in each case they found they were fighting pillars, windows, roof lines, each of which was placed to be used differently. If we weren’t embodied beings, that wouldn’t matter – a room is a room, no matter which way round the seats are placed – but we are, and we know, you know, it does.

That disquiet may be a price you are willing to pay, but don’t fool yourself that it isn’t a price.

Let’s take it one step further.

The essence of the Modern or International architectural style is that it is utilitarian. See it in Le Corbusier’s famous line, that homes are machines for living in. What does that say about the idea of a home? What does that say about being human?

The prevalence of this style in architecture has worked its what through to a preferred minimalism and utilitarianism in every aspect of life – no decoration, no beauty. In fact, no decoration is beauty.

And so we need to ask to what extent evangelical theology has breathed in this atmosphere, and allowed itself to be shaped by it.

I’ve been in services where we have moved from element to element as if they had been bolted together using an Allen key.

I’ve been in services where we have moved from element to element as if they had been bolted together using an Allen key.

I’ve been in church buildings where – even brand new – their only virtues were cleanness and spareness. Antiseptic, and cold. Easy to clean, but not easy to love.

I’ve read hundreds of Christian books which showed no variation in size or font between them, and offered zero visual stimulation, even on the cover.

I’ve heard (I’m sure I’ve preached) sermons where the only goal was clarity and simplicity, to the exclusion of depth, or wonder, or difficulty.

Now, I’m on dangerous ground here, because we all know there is spiritual peril in rhetorical style. Now, all our preaching has a rhetorical style – even if we are trying to be as simple as possible. Simplicity is a stylistic choice and places constraints on us. We choose words, craft illustrations with care. At least I hope we do – I hope no-one thinks that a story told one way will be as effective as a story told in any way. We all design our material.

And the danger is that we, or our hearers, fall in love with a style. Back in the day, people would applaud particularly beautiful phrases or apposite (and obscure) quotation. We, on the other hand, applaud those who are Tik-tok ready.

Plainness and simplicity is also a style, and one that also contains its worldview.

So we need to say – again – that plainness and simplicity is also a style, and one that also contains its worldview. That says that the bible is basically straightforward (when I would actually want to say that it is profoundly coherent, but the reason it is satisfying for life is that you can’t plumb its meaning on first reading). That says, if you have questions, we have answers (when I actually want to say, God has revealed many answers to many questions, but he also has questions he wants to ask you). That says, God’s truth can be presented as a series of bullet points (when I actually want to say that it can be, but it might also be a poem, or a parable, or a prophecy, and sometimes bullet-points kill).

I’m not arguing for baroque, or gothic, or curlicued fancies in our preaching – any more than Heatherwick is arguing for that in a buildings.

I’d just like a little more self-awareness in our worldview. An awareness of how it might be limited and limiting. And maybe some delight.

You can buy Humanise from Amazon here Heatherwick

Have you read it? What did you think? Pile in!

Thank you Chris. This is excellent as ever.

Cheers, Mark

Thanks Chris.

Thanks Chris, a really helpful and provocative read.