Our task is not merely to exegete the scriptures, but to exegete the cultural moment we inhabit, by their light, so that the bible sparkles with its built-in relevance.

So when an art exhibition has long queues outside for months, I want to suggest it is worthy of our attention, as much as any blockbuster movie or best-selling book. And that’s been the case with David Hockney’s retrospective Drawing From Life at the newly-refurbished National Portrait Gallery, just off Trafalgar Square.

It is a cultural moment, worthy of biblically-informed exegesis.

David Hockney was one of the group of artists who burst into the British art scene in the 60’s. His trademark bright colours and clean lines were obvious from the outset, and only enhanced with a move to California and life in the sun. Fluorescence, and neon, were added to the mix, along with the lifestyle of the time.

He’s probably the most recognisable British artist of our day, by some distance.

Like his hero, Picasso, Hockney was prodigiously gifted from the outset, able to draw with a masterly competence in his teens. And like Picasso, I think that is one of the keys to his restless curiosity and experiments, because if producing jaw-droppingly excellent drawing was obviously so easy, it would have been boring to give his life to it.

And, also like Picasso, he is deeply immersed in art history and theory even while he seems to be breaking the rules. Most famously, he has championed the idea that the great masters didn’t simply sit with a blank canvas and produce stunningly accurate works. The breakthroughs that liberated scientists, particular the grinding of lenses and the manufacture of good mirrors, liberated artists too. Although they kept it often as a trade secret, because the mystique of the skilled and gifted artist is a valuable one. Find his stuff on YouTube – it’s compelling.

One more comparison – like Picasso, he simply cannot stop producing work.

I reckon there are three themes which mark his work, and make it instantly recognisable even while it keeps moving. I don’t want an algorithm to hit and sue me for reproducing copyright work (all the ones Ive used are publicity shots), so I’ll just suggest you grab your favourite search engine and scroll.

The first is a mastery of line. Whatever means he uses to produce them, Hockney’s simple pen drawings are astonishingly clean and confident. These are pens and inks which allow no erasing, and yet his line is sharp and deceptively simple, and error-free. This man can draw.

The second is a vibrancy of colour. Acrylic paint was new at the time he started, and it is able to give a quick, solid and vibrant colour block. Initially Hockney was grouped with the Pop Art movement, but I reckon his use of colour has moved way beyond that. Whether it’s the Grand Canyon or the winter landscapes of Yorkshire, he uses the kind of palette which has developed beyond even what the Impressionists were playing with, because of the new range of extreme colours available. He juxtaposes the most unlikely shades, and yet in his hand they are persuasive and lovely.

And the third theme is his constant restlessness of technique. He draws and paints, but then he broke new ground with the Polaroid camera, playing with perspective and points of view, and then again with his early adoption of digital painting on an iPad. He used new colours as they came on the market.

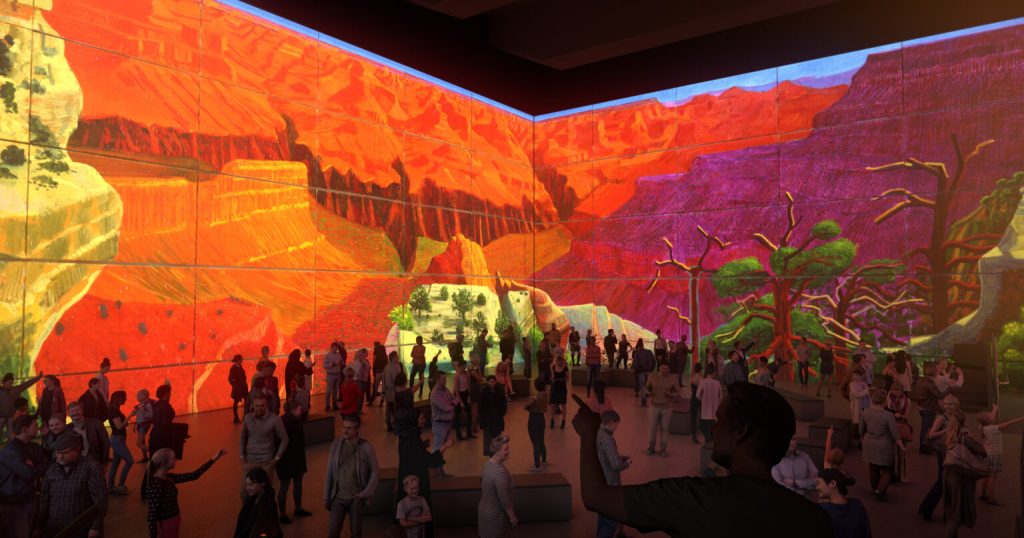

There was recently another London exhibition of his work, Bigger and closer (not smaller and further away) which was immersive, being projected on huge indoor walls, while those inside the space watched films and interviews. Here was the breakthrough: Hockney realised that by using an iPad he was able to recreate the way he worked, stroke by stroke. So you could watch the painting develop before your eyes, designed for the brightness and luminosity that projection can achieve. He did that in his eighties.

These three themes seem to move around three main areas of work: landscape, stage design and portraiture. I’m sure there are many others, but those three seem especially prominent and have remained constant, up to the present – stage design less so of late.

The exhibition of portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery is a moment to assess his work – and to do so as Christians, exegeting our culture. What does the phenomenon of Hockney, so wildly popular and so very good, tell us? And how, as pastors and preachers, can we learn, and speak?

Hockney tells us – no, shows us – that our world is staggeringly beautiful, even at its most apparently mundane. A damp road in winter. Two people and a cat. His eye for what is there, and the colours which make up what is there, should make us pause. If we need to be reminded of the gorgeousness of creation, and of people, Hockney wakes us up.

Look, he keeps saying. Just, look at the world.

If your view of the world is becoming jaded, let him show you. True, he turns the colour up, but once he’s done it you can see what he’s getting at, and it’s hard to dial it back again.

And that’s true, if your world is becoming predictable. Let me show you, Hockney will say, how to see your familiar scenes with different eyes.

And if ministry is becoming repetitive, he will challenge you how you might adapt, try new things, without ever leaving the authenticity of your particular style. There is an underlying (I don’t want to push this too far, but my artist friends are nodding) honesty, and integrity to his work. Line, colour, form, tone – they all work, even when he is at his most experimental. I would love to be as unstuck-in-a-rut as Hockney.

I would love to be as unstuck-in-a-rut as Hockney.

That requires two elements. First, there is raw talent. He drew with astonishing skill, early. You might have been able to preach well, from a young age; people commented on your clarity and structure when you were in your teens or twenties. Good – God gave you that talent. But Hockney then learnt, relearnt, challenged himself, added skill to talent, and then more skill, and more again. Is that your pattern? Or are you basically operating with the skill set you learnt at college? Do you need to take a course in counselling, or story-telling, or how to make great visual aids, or preaching to camera? Skill up?

Hockney will then show you how to treat people with warmth and generosity. In all the portraits in the exhibition, I don’t recall one which was cold, or formal, or treated his subjects as a mere surface to explore (if you’re interested, I’m contrasting him with Lucian Freud, whom I find cold). Each one was of a sitter, engaging with the warm and friendly artist – unless the subject was asleep. It would be hard not to like Hockney, and Hockney likes people.

Pastor, are you hearing this?

Now, let’s add some theological perspective into the mix. I have no extant knowledge where Hockney is, spiritually, although it’s not hard to discern aspects of a lifestyle and a worldview that would not sit easily with standard evangelicalism, if not reject it. He has never been shy about his sexuality, for instance.

There is nothing unusual in that. In fact that will be true of any cultural artefact we consume, even if we live in a Christian bubble. We always have to add a lens, operate at a cleaning distance, think critically. Sometimes the artefact is, on reflection, one that is too disturbing for us personally, and we choose to be separate, for our own sake. There are books, movies, artists, TV shows, I have chosen not to taste.

But I’d maintain that Hockney is a shining example of the skills and gifts God has scattered so generously in his world, and of the paintbox he has placed in our hands.

Can we enjoy the good work of an unbeliever? (Remember, if you say no, that that means you can never enjoy a great meal, or a good wine, or a beautiful garden, or a fantastic dance, or a funny cartoon, or, or, or).

If I want put Hockney in a biblical frame, I’m plumping him into Ecclesiastes. Because to my eye, he shows us the beauty and pleasure and colour of life, under the sun. I don’t see Hockney dealing in anything metaphysical or beyond. There’s no mystical allegory here, no clue to a deeper meaning. All is a gorgeous ‘now’.

All is a gorgeous ‘now’.

And maybe that’s the challenge to speak into. If we are used to casting the gospel in terms of what people lack, and the missing element of their life, we need to be able also to speak to those whose life is full, and enjoyable and pleasurable. For whom the world is not about greed, but about delight. It’s not ashen – it’s rainbow coloured, without any irony or subterfuge or agenda.

It just is, in its loveliness.

I think that’s why he is so popular in the 21st century, because it is a straightforward, uncynical approach to life under the sun.

And so our task is to point to the dazzling creator, the beautiful saviour, the gift-giving Spirit, the multi-splendoured nature of God’s gospel, the one who made and gave us the paintbox, and has infinitely more to share.

Are you up for the challenge?